Education Disrupted

Leveraging the Lessons of a Pandemic to Design the Future of Learning Environments

The past year had its own lesson to teach the education system. After schools pivoted their entire educational infrastructure from in-person learning to virtual teaching essentially overnight, public health and education leaders are grappling with how to reopen schools in a post-COVID-19 learning environment. Schools need to address capacity, safety, flexibility, circulation, and student well-being differently than before—not only to protect students and staff throughout the remainder of the pandemic, but also to prepare educational infrastructure for potential future health crises.

To date, many of the implemented changes have been physical in form—a shift in location from in-person to remote learning, or the implementation of sanitizing and temperature checking stations. This focus on the protection of physical health was absolutely necessary in the face of the danger of COVID-19. However, limited resources across the board meant that while physical health protection took up the bulk of time, money, and energy, mental health protection was often unable to receive the same attention. And when it comes to the effects of isolation inherent in the physical protections implemented, mental health issues were largely unavoidable.

Remote learning has been difficult on children and their families, affecting quality of education as well as mental health. Widespread reports indicate that the well-being of remote learners has severely declined due to the isolation inherent to the pandemic. Studies show vast increases in suicidal ideation, upticks in pediatric emergency room visits, and widespread feelings of depression. Multiple stressors contribute to this including fear and worry about personal health and the health of loved ones, difficulty concentrating, disruptions to sleeping patterns, increased concerns of academic performance, and above all decreased social interactions due to physical distancing.

But for some students, particularly neuro-divergent students or students subjected to chronic bullying, remote learning has been a gift. Other students have found relief in not needing to adhere to a strict, early morning routine and are finally getting the sleep needed for proper development.

This is all to say that the educational system’s response to the pandemic both created and solved problems. Educational leaders are now tasked with building a new system that restores the safe socialization and benefits of in-person learning, without erasing the growth and positive outcomes remote learning has had for some of its most vulnerable students.

For a brief window of time, we have the opportunity to build anew. It is time to creatively address how technology, space, and systems can be reimagined to support the unique and differentiated needs of students. Changes throughout the past year have addressed the physical health protection of students—future iterations must also reckon with protecting and nurturing mental health within the educational system. bKL recognizes that there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and each school has created a unique path in response to their specific challenge sets. Our design solutions and examples below detail potential considerations and leading trends we can leverage from the pandemic to inspire a new brighter future for education design as the world moves forward.

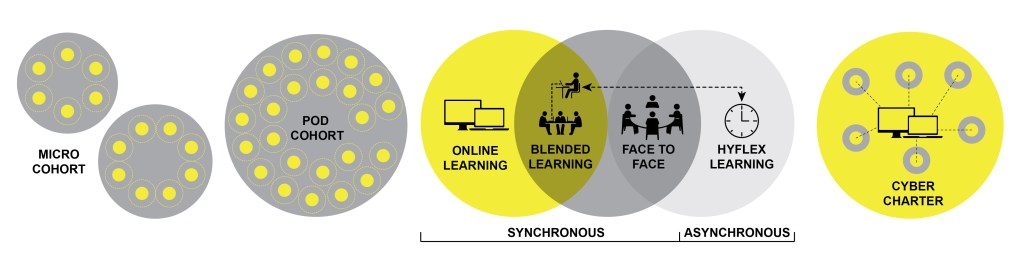

EMERGING LEARNING MODELS

The COVID-19 Pandemic has shifted the teaching landscape to provide alternative opportunities for children who struggle in a “traditional” classroom setting, and has provided lessons that can be leveraged to inform the future design of learning environments for more positive outcomes. In the next 5 years, some educators we interviewed believed we will continue to see blended and online learning without 100% adoption of in-class learning. Regardless, we as designers need to create spaces that are equitable, inviting and inspiring to encourage collaboration, curiosity, and belonging.

When considering needed changes to learning environments, school boards might be hesitant to pursue mega referendums until there is a better understanding of both the duration as well as long-lasting ramifications of the virus. When considering investment in built spaces versus retrofit, there are varying degrees of change that provide flexibility in options for educational leaders.

These organizational options address the diminished instructional capacity due to social distancing requirements, as well as the impact of social distancing on collaborative learning. In a typical classroom, social distancing suggests that desks should all be turned in the same direction, rather than facing each other, to reduce transmission from virus-containing droplets. However, this directly contradicts project-based, student-centered learning whereby students sit and work together to encourage teamwork and face-to-face discourse.

Beyond the traditional classroom, here are examples below of other teaching methodologies that will inform design.

Micro Cohort

A cohort is a collaboration-focused group of students who work together to progress through an educational experience. This learning model facilitates social interaction and collaboration with peers at an intimate scale, hence the name “Micro Cohort.” Denmark, for example, was the first country in Europe to use this model when reopening its primary schools after containing the virus early on. They assumed that social distancing would be unreliable with young children, so instead children stay in small groups of up to a dozen all day, in "protective bubbles." These micro-groups of pupils arrive at a separate time, eat their lunch separately, stay in their own zones in the playground, and are taught by one teacher. In order to implement this model, schools can adapt existing classrooms or common areas such as libraries and cafeterias by creating smaller, more intimately scaled zones with low furniture arrangements, plexiglass barriers or moveable screens. These visual boundaries define safe space for micro-cohorts to engage in personalized learning and social interactions on an intimate scale.

Pod Cohort

A larger version of the Micro Cohort is the Pod Cohort. Larger group cohorts provide catalysts for new insights, collaboration, motivation and support. At Chicago Public Schools (CPS), their classroom strategy is limiting students to a “pod” with 24-30 classmates. The pod stays in the same classroom all day and does not interact with students in other pods—especially during lunch, which according to the CDC is the highest risk of spread. For special needs students, they have developed Cluster programs that occur in smaller break out rooms adjacent to classrooms where teachers can work in groups of 6-8 or one-on-one. The pod cohort model can be implemented in a typical classroom by creating flexible arrangements of gathering space for informal, collaborative learning. For instance, desk groupings that honor social distancing can be paired with mobile markerboards to expand the range of teaching/learning modes. Wall-facing seating allows for individual, private activities while reconfigurable, moveable tables foster team-oriented activities and agile collaboration.

Blended

Blended, or Hybrid, learning models address the problems with socially-distanced learning by significantly reducing class sizes as well as incorporating remote learning. Most pupils spend about half their time in class and half learning at home. Scheduling options for this are flexible: half day shifts, alternating days or even alternating weeks, and staggering of arrival, departure, and break times. This mode necessitates highly flexible classroom space that is easily reconfigurable to accommodate varying student populations. In Blended learning, the physical classroom morphs into a production studio of sorts due to enhanced distance technology demands such as cameras, microphones, and displays to support teaching and learning, whether in person or virtual.

Hyflex: Choice & Independence

The emerging approach that has garnered national attention is the Hyflex model (hybrid/flexible). This approach enables a highly flexible participation policy for students, whereby students may choose to attend face-to-face class sessions in-person in a traditional classroom or online at the same time (synchronous), or complete course learning activities online at any time or place (asynchronous). The instructor delivers the class in a regular classroom, but the students may attend in person, participate in the class through video conferencing, or watch a recording of the class session at any time. This model provides the most flexibility for students. From the instructor’s perspective, it can be challenging because you need to plan for multiple audiences. Effectively teaching with this model requires much more planning than teaching to a regular class or even to an online-only class.

Cyber Charters: A Bullying Refuge

Nearly one in four kids will be bullied at some point in their adolescence, and approximately 160,000 will skip school each day to avoid being bullied. Many students and parents, in search of a safer option, have turned to online learning as a refuge from the bullying experienced in traditional brick-and-mortar schools. While online learning is just one way of dealing with bullying, many parents and students find it to be extremely effective. When it comes to bullying, online high school and middle school programs allow students to study in the privacy of their home (or in a library or a coffee shop) away from the peers who are targeting them. Not only does it provide a safe environment for them to continue their schooling, but it also provides an opportunity to study at their own pace. More than 4.5 million kids are enrolled in K-12 online schools nationwide which has skyrocketed from a decade ago when only 50,000 students in the U.S. were utilizing online schools. The options for alternative educational opportunities are growing and will shape the landscape of teaching and learning in interesting ways as we look to the future.

NATURE-CENTRIC ENVIRONMENTS

Due to the reduced risk of transmission in the outdoors, some schools have taken advantage of outdoor learning as part of their curriculum and infrastructure. This solution has the dual benefit of providing social distancing and easing the load on teaching areas and circulation zones within school buildings, along with the well-documented improvements to health through connection to the outdoors.

While this may seem at first to be a more practical solution for rural schools, city schools are also taking advantage of safe implementation of outdoor learning. Urban schools can leverage rooftops, parks, and museums, with the added benefit of fostering an appreciation for and understanding of the civic resources available to the students within their communities.

Schools are developing a vast array of programmatic tie-ins to their outdoor setting, like Littlewood Elementary in Florida where students observed bird behavior, calculated the dollar value of trees, measured plant growth and collected data on seasonal changes. Green Schoolyards America has also developed the National Outdoor Learning Library—practical resources for taking school outside during the pandemic and beyond. Students can be given ownership to design and create their own outdoor learning area. These examples and programmatic support offer a great opportunity for schools to implement creative solutions that better the education and experience for their students.

THE NEW FRONT PORCH

As schools reopen, the entry procession and drop-off sequence has to be rethought to address increased complexity with queuing, circulation, safety and security protocols. One solution is to create the addition of a "front porch," or a welcoming “town square” area that readies students, teachers, and visitors for entering the school. Not only will such structures provide shelter to those queuing to get inside, it will also serve as a zone for administrators to check temperatures, distribute masks and sanitize.

Some existing schools are adapting the limited entry space they have to include these functions. For instance, at the GEMS World Academy, the parent “hang out rooms” are being repurposed as screening areas for students because parents aren’t currently permitted past the front doors. Similarly at CPS, they initiated protocols at the entries including temperature checks for all visitors and online screening through a health screening questionnaire.

The challenge before schools is how to incorporate this welcoming “front porch” methodology and implement it at a scale and fluidity suitable for school children. With social distancing and hundreds of students entering at once, this could quickly feel like an unwelcoming cattle call. A more fluid, organic model allows for humanity and engagement balanced with the necessary safety and security precautions. By allowing student choice, the entry procession can be an invitation to welcome and support students, while building a sense of community and belonging.

LOOKING AHEAD: BALANCING DIFFERENTIATION AND EQUITY

Educational systems today face the enormous challenge of reopening schools in a way that not only protects the safety of the students and staff, but also doesn’t forget the lessons taught by the pandemic. While some necessary changes had devastating consequences for students, other students thrived in remote learning or outdoor settings.

An equitable approach, paradoxically enough, necessitates differentiation. Different students have different needs, and exist within widely ranging contexts. As schools move forward into a new generation of learning, we must move away from a one-size-fits-all approach, and instead implement flexible, efficient systems that can be easily tailored to meet the individual. This includes considering both the physical and mental health needs of the student body, as well as how to incorporate supportive, community-engaged learning in every context. The pandemic, for all its destruction, has given us the space to imagine a better way forward. We owe it to future generations to not waste the opportunity.